-

Which the release of FS2020 we see an explosition of activity on the forun and of course we are very happy to see this. But having all questions about FS2020 in one forum becomes a bit messy. So therefore we would like to ask you all to use the following guidelines when posting your questions:

- Tag FS2020 specific questions with the MSFS2020 tag.

- Questions about making 3D assets can be posted in the 3D asset design forum. Either post them in the subforum of the modelling tool you use or in the general forum if they are general.

- Questions about aircraft design can be posted in the Aircraft design forum

- Questions about airport design can be posted in the FS2020 airport design forum. Once airport development tools have been updated for FS2020 you can post tool speciifc questions in the subforums of those tools as well of course.

- Questions about terrain design can be posted in the FS2020 terrain design forum.

- Questions about SimConnect can be posted in the SimConnect forum.

Any other question that is not specific to an aspect of development or tool can be posted in the General chat forum.

By following these guidelines we make sure that the forums remain easy to read for everybody and also that the right people can find your post to answer it.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MSFS20 Kennedy Space Center Scenery for MSFS2020

- Thread starter Misho

- Start date

- Messages

- 65

- Country

Those are SERIOUSLY impressive sequences and VFX, man! I dare say, these are best in-game launch sequences, hands down (and I used KSP, KSP2, Orbiter, Re-Entry, and Space Flight Simulator)

Now - please release it.

And... let us ride to space, too

Now - please release it.

And... let us ride to space, too

- Messages

- 1,014

- Country

We’ve been approached by a few YouTubers who wanted to make feature/promo videos of KSC Scenery, especially since we started posting videos of the V2 features.

Here’s a PREVIEW of the upcoming V2 features, made by one of our biggest fans, FS YouTuber Fast Times Vero. He is definitely excited

( no monies were paid by us for this video )

)

Here’s a PREVIEW of the upcoming V2 features, made by one of our biggest fans, FS YouTuber Fast Times Vero. He is definitely excited

( no monies were paid by us for this video

- Messages

- 1,025

- Country

Misho congrats this is awesome. I'm working on a movie set back in the days of the Saturn/Apollo missions to the moon and this will help me to figure out where to build the scenes and camera blocking. Plus I can't wait to see the launches in 3D in VR.

I have one question for you (and it's asked with all due honor and respect and awe at your amazing work) as I know it's a preview in the last two videos, are the trajectories after the roll maneuvers still work in process?

Space Shuttle Tracjectory

I have one question for you (and it's asked with all due honor and respect and awe at your amazing work) as I know it's a preview in the last two videos, are the trajectories after the roll maneuvers still work in process?

Space Shuttle Tracjectory

- Messages

- 1,014

- Country

Hi, and thanks!!Misho congrats this is awesome. I'm working on a movie set back in the days of the Saturn/Apollo missions to the moon and this will help me to figure out where to build the scenes and camera blocking. Plus I can't wait to see the launches in 3D in VR.

I have one question for you (and it's asked with all due honor and respect and awe at your amazing work) as I know it's a preview in the last two videos, are the trajectories after the roll maneuvers still work in process?

Space Shuttle Tracjectory

View attachment 96664View attachment 96665

No, the trajectories are basically done. Why do you ask?

- Messages

- 1,025

- Country

Hi, and thanks!!

No, the trajectories are basically done. Why do you ask?

Just I noticed in the videos that they were going straight up on launch and in real life they actually immediately start moving towards the atlantic immediately after clearing the tower., even the space shuttle, you can see their trajectories in the above photos (top is the Space Shuttle and the second is Starship. The reason being is that they want to move them away from being directly above the launch towers in case of a RUD, they don't want the towers destroyed in real life. I figure it may not take much to set waypoints to start that arc movement. And again I mean no disrespect and just make the suggestion out of complete honor and awe at the work you are doing.

Unfortunately they don't make the lat/lon data available for launches publicly, but I may be able to ask a friend of mine who works (or worked) at NASA training astronauts if she may know who I can reach out to, otherwise I can get out to the cape at Playa Linda Beach and Film a Launch and do some calculations to map out the launch tracjetories accurately. Another friend's father worked on the Saturn/Apollo missions and may be able to help, then there's another friend who's father was the head of the Space Shuttle Design program, so I may have a few good contacts.

Love your work though Misho and I share in absolute humility before you with the greatest respect and utmost honor.

P.S. If you notice the main engines on the Space Shuttles, they deflect thrust to push the Shuttle forwards of the tower, once they initiate the roll then it helps continue pushing out over the atlantic see image below

Best seen in this video at 1:33, we can see it moving to the right laterally as it ascends off the launch pad

Last edited:

- Messages

- 1,014

- Country

Thanks Dean!

I appreciate the info, but I do think that they go straight up for a while to clear the tower (with a bit of a forward slide), then they do a roll maneuver, then pitch. They do not pitch over immediately, I am sure of that. The pics that you show are extreme distances, so the bit where it goes straight up is tiny compared to the rest of the trajectory, and not clearly visible. There are plenty of launch videos where the space shuttle goes straight up, then rolls, then pitches, actually, just like in the video you provided, where you can clearly see that it goes straight up for a while (and a bit forward), and then it rolls and pitches. Same goes with Saturn V and Artemis.

Most rockets, when launching, performs two essential maneuvers, sometimes called roll/pitch program:

Oh - and I don't use waypoints for this. I use simple 3D vector physics to define the motion of the shuttle, kind of a pseudo astrodynamics.

I appreciate the info, but I do think that they go straight up for a while to clear the tower (with a bit of a forward slide), then they do a roll maneuver, then pitch. They do not pitch over immediately, I am sure of that. The pics that you show are extreme distances, so the bit where it goes straight up is tiny compared to the rest of the trajectory, and not clearly visible. There are plenty of launch videos where the space shuttle goes straight up, then rolls, then pitches, actually, just like in the video you provided, where you can clearly see that it goes straight up for a while (and a bit forward), and then it rolls and pitches. Same goes with Saturn V and Artemis.

Most rockets, when launching, performs two essential maneuvers, sometimes called roll/pitch program:

- Roll program aligns the rocket with the correct azimuth for a desired orbital inclination

- Pitch program leans the rocket into what is called a gravity turn, essentially, without it, rocket would go straight up, never achieving orbit.

Oh - and I don't use waypoints for this. I use simple 3D vector physics to define the motion of the shuttle, kind of a pseudo astrodynamics.

Last edited:

- Messages

- 2,226

- Country

Amazing !!!! its looks soo good manMore video goodness from one of our fans:

- Messages

- 1,025

- Country

Thanks Dean!

I appreciate the info, but I do think that they go straight up for a while to clear the tower (with a bit of a forward slide), then they do a roll maneuver, then pitch. They do not pitch over immediately, I am sure of that. The pics that you show are extreme distances, so the bit where it goes straight up is tiny compared to the rest of the trajectory, and not clearly visible. There are plenty of launch videos where the space shuttle goes straight up, then rolls, then pitches, actually, just like in the video you provided, where you can clearly see that it goes straight up for a while (and a bit forward), and then it rolls and pitches. Same goes with Saturn V and Artemis.

Most rockets, when launching, performs two essential maneuvers, sometimes called roll/pitch program:

The reason they can't pitch over immediately is because the rockets, at least on launch pads 39A/B, are oriented to face the north. If the orbital trajectory requires, say, orbital inclination of 60 degrees, the rocket needs to roll 60 degrees, and only then pitch into the gravity turn. So, it would be impossible for a rocket to pitch into a gravity turn at 60 degree azimuth, without aligning itself using a roll maneuver. The rockets have gimbaled engine nozzles, but just like aircraft, they pitch up and down, so when they are upright, they need to roll in the direction of the azimuth, and only then pitch into gravity turn.

- Roll program aligns the rocket with the correct azimuth for a desired orbital inclination

- Pitch program leans the rocket into what is called a gravity turn, essentially, without it, rocket would go straight up, never achieving orbit.

Oh - and I don't use waypoints for this. I use simple 3D vector physics to define the motion of the shuttle, kind of a pseudo astrodynamics.

I just want to say first, I am in no way disrespecting your awesome work, I just love your passion and know you care about this stuff and sharing the launches with the world as accurately as possible. I'm just providing information that may help you in your quest.

The reason they can't pitch over immediately is because the rockets, at least on launch pads 39A/B, are oriented to face the north

That's note entirely correct the Shuttle is aligned East/Northeast (aka ENE), it's aligned parallel to the shore:

Code:

This orientation was intentional:

- Launches are directed eastward to take advantage of the Earth's rotation, which gives an extra velocity boost, making launches more fuel-efficient.

- Facing east allows the shuttle to enter the desired orbit (usually inclined slightly to the equator) while safely flying over the ocean rather than populated land areas.I promise you they don't go straight up, even the saturn/apollo, but I'll have to gather the proof for you as soon as they clear the tower they start to arc and move away from the launch pad towards the Atlantic. I've been to multiple launches. I have friends at NASA so I'll gather the proof. They don't pitch over immediately, but they do definitely start a trajectory over towards the atlantic. You can see the Space Shuttle in the side on launch views how it moves towards the atlantic in the video, and the angle of the main nozzles push the shuttle east of the tower immediately upon release. You can see that for yourself in the side on views of shuttle launches, the entire ship slides forward of the tower and you can use the lightning mast at the top of the launch tower for reference. Also the roll maneuver for the Space Shuttle happens 6 seconds after lift off and again the main engines help push the shuttle over onto it's back. It's even there in the official NASA photos, you're saying you believe it goes straight up but the official photos prove otherwise.

Sigh, I only interviewed to work at SpaceX and have friends at NASA, I'm not making this stuff up. If you dig into it you'll find it yourself. But I will go talk to the engineers and friends I have at NASA who actually work on the programs and will come back with proof once I have the time. I'm working on 3 movies right now so time is limited but I'll try talking with Donna who trains the astronauts to use the system and I'll get up to Playa Linda Beach with a high def camera side on to the tower and bring it into my cinema edit suite and show you the image analysis once I have time.

I get it, no one likes being told about errors... And as I said I have total respect for your work but you may want to consider I'm telling you the truth about the launches. I'm not here to dis your work or anything, but it's like someone who handles money every day, you know what the real thing feels like and looks like, you don't study counterfeits, you study the real thing and when a note that's not genuine comes across your path it stands out like a sore thumb. It's the same thing with the launches, I've seen many close up, I've got friends who work in key roles at NASA and I've got over 100 years of NASA Technical Reports in my library.

But I don't think I'm going to be able to convince you until I provide empirical undeniable evidence.

EDIT: If you look closely at the Saturn/Apollo launches you'll notice the rocket starts moving at a slight angle (a couple of degrees) even before it clears the launch tower. It's in several high resolution films in slow motion and while I don't have time to jump into photoshop right now to show the correlation, it can be seen quite easily, there's also the beginnings of a very slow roll as it is clearing the tower that can be seen in other camera angles

Here is a better shot showing the angle of the rocket vs the launch tower here's the film if you'd like to observe

Here is a real time film of the Saturn launch, and the roll starts moments after clearing the tower at approx 10 seconds.

If we look at the Apollo 11 launch in real time we note the roll program happens about 13 seconds into the launch

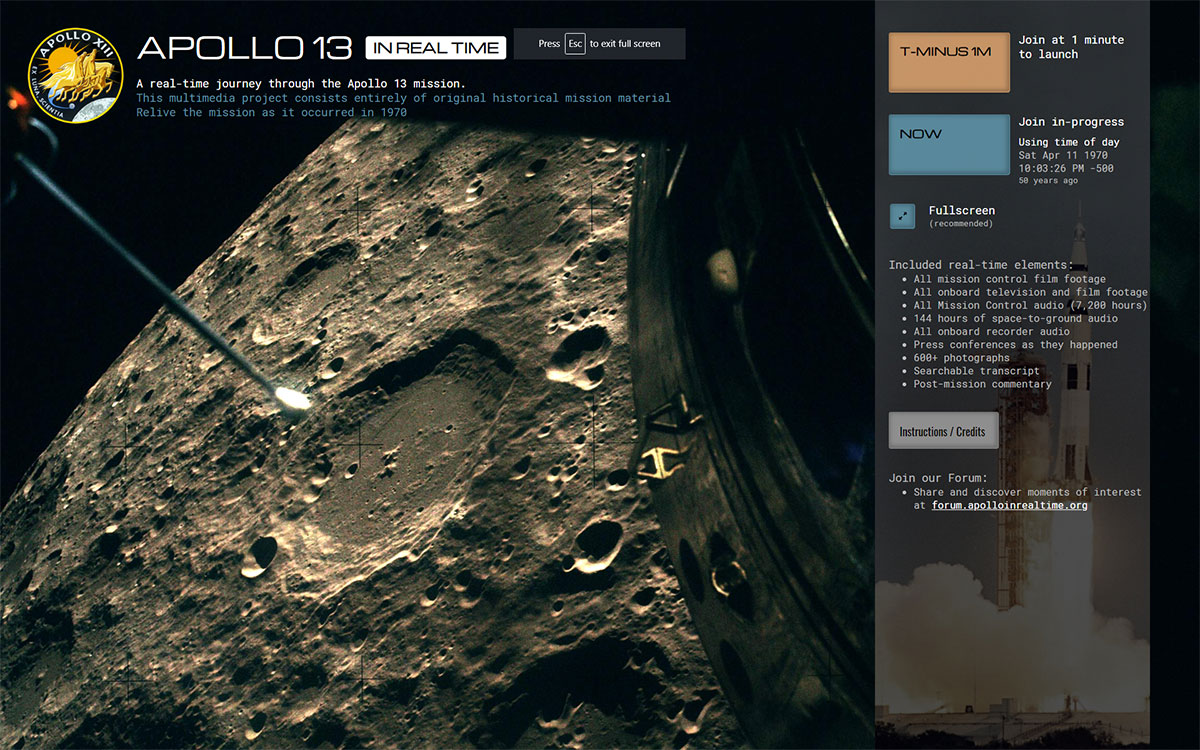

If we look at the Apollo 13 launch in real time we note the yaw program begins at T plus 5 seconds and the yaw program finishes at 14 seconds followed immediately by the roll program.

Apollo 13 in Real Time

A real-time interactive journey through the third lunar landing attempt. Relive every moment as it occurred in 1970.

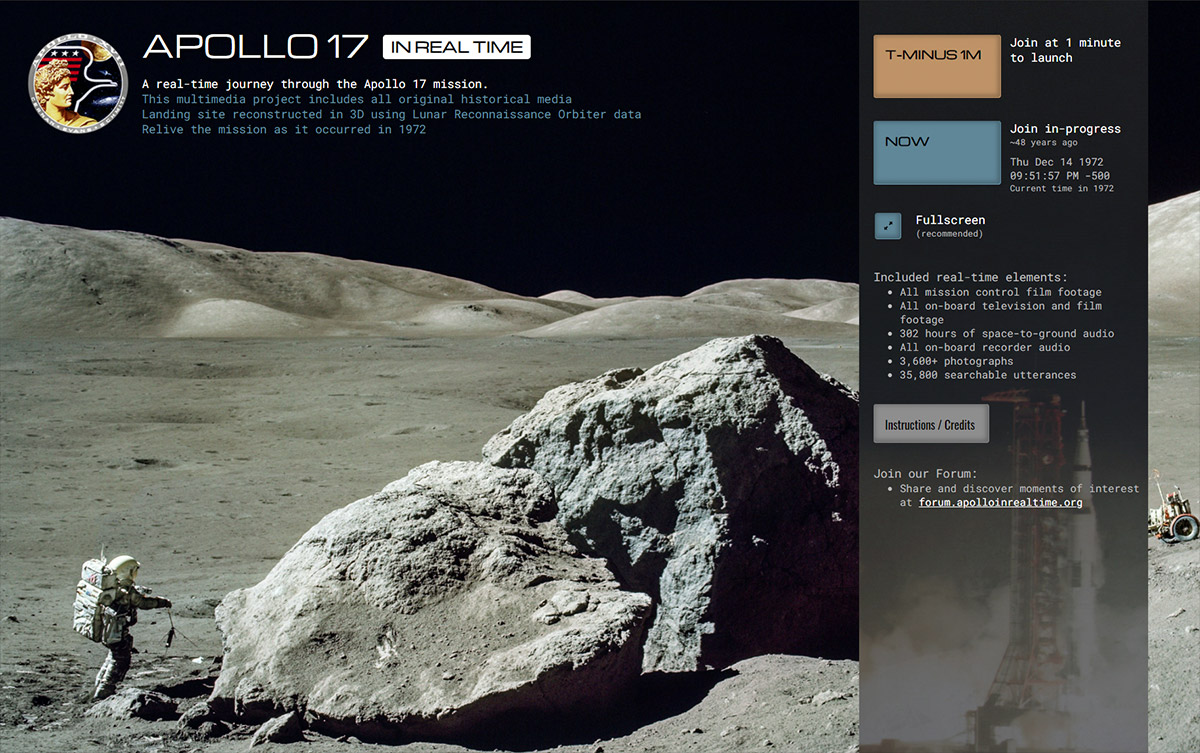

If we look at the Apollo 17 launch in real time we note the yaw program begins at T plus 1 second and the yaw program finishes at 10 seconds followed immediately by the roll program.

Apollo 17 in Real Time

A real-time interactive journey through the last landing on the Moon. Relive every moment as it occurred in 1972.

### Key Points

- Research suggests the space shuttle starts moving towards the Atlantic Ocean immediately upon lift off.

- It seems likely the shuttle does not go completely straight up, instead following a curved trajectory eastward.

- The evidence leans toward safety and orbital mechanics driving this path, with SRBs landing in the Atlantic by T+123 seconds.

#### Launch Site and Direction

The space shuttle launched from NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, on the eastern U.S. coast, next to the Atlantic Ocean. Launches were designed to go eastward over the ocean for safety, ensuring debris from failures would land in water, not populated areas.

#### Trajectory Details

At T+7 seconds, the shuttle rolls to a heads-down orientation, gaining horizontal velocity, not going straight up. By T+123 seconds, Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) are jettisoned and land in the Atlantic, confirming the shuttle is over the ocean early in flight.

#### Supporting Evidence

NASA's documentation and mission reports show the shuttle's path arcing over the Atlantic, with SRBs recovered from the ocean, supporting the eastward trajectory for safety and efficiency.

---

### Survey Note: Detailed Analysis of Space Shuttle Launch Trajectory

This detailed analysis explores the space shuttle's launch trajectory, focusing on whether it immediately moves towards the Atlantic Ocean upon lift off and whether it goes completely straight up. The investigation draws from NASA's official records, technical descriptions, and related articles to provide a comprehensive understanding, suitable for presenting to skeptics.

#### Context and Launch Site

The space shuttle program, active from 1981 to 2011, launched from NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, located on the eastern coast of the United States, directly adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean. This coastal location was strategically chosen for its proximity to the equator, which maximizes the benefit of Earth's rotation for launch efficiency, and for safety reasons, allowing launches to be directed over the ocean.

Launches from KSC were typically eastward to align with orbital mechanics and ensure that any debris from a potential failure would fall into the Atlantic Ocean, minimizing risk to populated areas. This practice is consistent with other East Coast launches, such as those by SpaceX, where first stages often land on droneships in the Atlantic.

#### Initial Launch Trajectory and Movement

The space shuttle did not launch straight up but followed a carefully designed trajectory that combined vertical ascent with horizontal movement. According to NASA's technical documentation, the launch sequence included the following key phases:

- **Liftoff and Initial Vertical Ascent**: The shuttle launched vertically, powered by two Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) operating in parallel with the orbiter's three RS-25 main engines, fueled from the external tank (ET).

- **Early Roll Maneuver**: At approximately T+7 seconds, at an altitude of 110 meters (350 ft), the shuttle rolled to a heads-down orientation. This maneuver was critical to reduce aerodynamic stress, improve communication and navigation, and begin gaining horizontal velocity. This roll indicates the shuttle was not going straight up but was already starting to arc eastward.

- **Throttle Adjustments**: At T+20–30 seconds, at an altitude of 2,700 meters (9,000 ft), the RS-25 engines were throttled down to 65–72% to manage maximum aerodynamic forces at Max Q, further shaping the trajectory.

- **SRB Jettison and Atlantic Confirmation**: At T+123 seconds, the SRBs were jettisoned at an altitude of 46,000 meters (150,000 ft), reaching an apogee of 67,000 meters (220,000 ft) before parachuting into the Atlantic Ocean. This event is significant because the SRBs' landing in the Atlantic confirms that by this point, the shuttle was already over the ocean, having moved eastward from KSC.

The RS-25 engines continued the ascent, with throttling adjustments at T+7 minutes 30 seconds to limit acceleration to 3 g, and main engine cutoff (MECO) occurring at T+8 minutes 30 seconds, with engines throttled down to 67% 6 seconds prior. Early missions used two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) firings to achieve orbit, while later missions used the RS-25 engines for optimal apogee, with OMS for circularization, with orbital altitudes varying from 220 to 620 km (120 to 335 nmi).

#### Why Over the Atlantic? Safety and Efficiency

The eastward trajectory over the Atlantic was driven by both safety and orbital mechanics. According to a Scientific American article ([Why Does NASA Launch Space Shuttles from Such a Weather-Beaten Place?](https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/space-shuttle-weather-florida/)), launches from KSC were directed over the ocean "to ensure the launch trajectory is over the ocean, avoiding populated areas that might get killed if debris dropped or the launch failed." This safety consideration was crucial, especially given Florida's low population density in the 1940s when the site was chosen, with Brevard County being mostly orchards, providing logistical advantages with nearby military bases.

Additionally, launching eastward takes advantage of Earth's rotation, which provides a natural velocity boost, reducing the rocket power needed. This combination of safety and efficiency explains why the shuttle's path was over the Atlantic from the outset.

#### Supporting Evidence from Various Sources

Several sources corroborate this trajectory:

- **NASA's Space Shuttle Overview**: NASA's official page ([Space Shuttle - NASA](https://www.nasa.gov/space-shuttle/)) details the program's history, noting 135 missions from 1981 to 2011, with launches from KSC, implying the eastward path over the Atlantic.

- **Wikipedia on Space Shuttle**: The Wikipedia page ([Space Shuttle - Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_Shuttle)) describes the SRB jettison at T+123 seconds, with recovery in the Atlantic, and mentions the trajectory's design for safety over water.

- **The Atlantic Photo Description**: An article from The Atlantic ([The History of the Space Shuttle](https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/07/the-history-of-the-space-shuttle/100097/)) includes a photo description stating, "The space shuttle twin solid rocket boosters separate from the orbiter and external tank at an altitude of approximately 24 miles. They descend on parachutes and land in the Atlantic Ocean off the Florida coast, where they are recovered by ships, returned to land, and refurbished for reuse." This reinforces the shuttle's position over the Atlantic early in flight.

- **Splashdown Practices**: The Wikipedia page on Splashdown ([Splashdown - Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Splashdown)) notes, "The American practice came in part because American launch sites are on the coastline and launch primarily over water," aligning with the shuttle's trajectory.

These sources collectively confirm that the shuttle's initial trajectory was eastward over the Atlantic, with the SRBs' recovery providing tangible evidence of its path.

#### Addressing the Skeptic's Doubt

For someone who doesn't believe the shuttle moves towards the Atlantic immediately and goes straight up, the key points to emphasize are:

- The roll to heads-down orientation at T+7 seconds shows it's not straight up but gaining horizontal velocity.

- By T+123 seconds, the SRBs landing in the Atlantic prove the shuttle is over the ocean, as they are jettisoned from the shuttle's path.

- The launch site's location and safety requirements necessitate an eastward trajectory, supported by NASA's documentation and historical records.

#### Conclusion

The evidence strongly suggests that the space shuttle, upon lift off, immediately starts moving towards the Atlantic Ocean and does not go completely straight up. It follows a curved trajectory eastward, rolling to a heads-down orientation within seconds and passing over the Atlantic by T+123 seconds, as evidenced by the SRBs' recovery. This path was driven by safety and orbital mechanics, making it a standard practice for launches from KSC.

---

### Key Citations

- [Space Shuttle NASA Overview](https://www.nasa.gov/space-shuttle/)

- [Space Shuttle Wikipedia Page](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_Shuttle)

- [Why NASA Launches from Florida](https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/space-shuttle-weather-florida/)

- [The History of the Space Shuttle](https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/07/the-history-of-the-space-shuttle/100097/)

- [Splashdown Wikipedia Page](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Splashdown)

Here’s links to two of the shuttle missions that outline the roll maneuvers and when they end…. The roll over commences at 10 seconds and is complete by 19 seconds with heads down orientation to give the trajectory to accelerate for orbital insertion… The PDF’s have moment by moment documentation of the maneuvers.

Last edited:

- Messages

- 1,014

- Country

That's ok, I love a healthy debate  Yes, I know about eastward launches - you get a bit of a pick-me up regarding the velocity, because Earth's spin gives you a bit extra. Every nation in the world launches Eastward, with a few exceptions for some specific reasons, or polar orbits that launch straight north.

Yes, I know about eastward launches - you get a bit of a pick-me up regarding the velocity, because Earth's spin gives you a bit extra. Every nation in the world launches Eastward, with a few exceptions for some specific reasons, or polar orbits that launch straight north.

). The shuttle is sitting on the pad, also aligned to the north. That is, prior to launch, orbiter's belly is pointing to straight north, and it's tail is pointing to straight south. There is no other way shuttle can be mounted on the pad, but strictly ALIGNED with the North-South pad... unless they rotate the MLP (mobile launch platform), completely re-route water piping, and re-dig the flame trench. But I will need photos of that as proof. Shore, or any other landmark, has NOTHING to do with how shuttle gets aligned. During the first phase of the launch, Shuttle rotates (rolls) by the exact amount required to get it into a desired orbital INCLINATION. That's all there is to it.

). The shuttle is sitting on the pad, also aligned to the north. That is, prior to launch, orbiter's belly is pointing to straight north, and it's tail is pointing to straight south. There is no other way shuttle can be mounted on the pad, but strictly ALIGNED with the North-South pad... unless they rotate the MLP (mobile launch platform), completely re-route water piping, and re-dig the flame trench. But I will need photos of that as proof. Shore, or any other landmark, has NOTHING to do with how shuttle gets aligned. During the first phase of the launch, Shuttle rotates (rolls) by the exact amount required to get it into a desired orbital INCLINATION. That's all there is to it.

AFTER they are launched, they climb for a while straight up (maybe with some drift), and then they do a roll, so that the orbiter's tail winds up at an angle of desired orbital inclination. Shuttle needs to be in the belly up, tail down orientation (so, below external tank, not on top) due to center of gravity and aerodynamic efficiency reasons. So basically, orbiter rides upside-down to orbit (and I think it stays upside down due to thermal dissipation issues)

Let's start from the beginning: It is VERY expensive (fuel wise) to change orbital shape (inclination, apogee/perigee...), while in space, so, when launching, launches are calculated so that they intercept desired target in orbit with the least amount of fuel expenditure. So, for example, ISS's orbital inclination is 51.6 degrees:

The space shuttle, in order to align with ISS , needs to rotate by 90 + 51.6 = 141.6 degrees (counter-clockwise). Trust me on this. This is orbital mechanics 101. Granted - there may be slight variations on the exact sequence (Looks like shuttle starts pitching while it is still rolling) but the essential principle is: Roll to desired azimuth, pitch into gravity turn.

The amount of azimuth rotation determines the inclination of the orbit. As stated, 141.6 degrees is required to intercept ISS. If the mission calls for a different profile, like a Hubble repair mission, (Hubble's orbit has an inclination of 28.5 degrees), the initial roll will be 118.5 degrees.

Note that anything launched from KSC will have at least 28.6 degrees orbital inclination, as this is the lowest inclination orbit that can be achieved at KSC's latitude (which is 28.6 degrees north). Optimal position of the launch site would be on equator, because from that location, orbit with any inclination angle can be achieved. That's why there was a company called Sea Launch, which would take the whole launch platform out to sea, to the equator, and launch from there.

Re: showing me a video where shuttle starts pitching right away, on the pad: There are 100s of videos of shuttle launches that show shuttle (or any rocket) going straight up for 10 or so seconds, before starting to roll. Are you telling me you will search for one video that shows otherwise, to convince me that 100s of videos are wrong?

No. You are reading this wrong. Both pads, 39A and 39B, are aligned PRECISELY to North (check the Google mapsThat's note entirely correct the Shuttle is aligned East/Northeast (aka ENE), it's aligned parallel to the shore:

AFTER they are launched, they climb for a while straight up (maybe with some drift), and then they do a roll, so that the orbiter's tail winds up at an angle of desired orbital inclination. Shuttle needs to be in the belly up, tail down orientation (so, below external tank, not on top) due to center of gravity and aerodynamic efficiency reasons. So basically, orbiter rides upside-down to orbit (and I think it stays upside down due to thermal dissipation issues)

Let's start from the beginning: It is VERY expensive (fuel wise) to change orbital shape (inclination, apogee/perigee...), while in space, so, when launching, launches are calculated so that they intercept desired target in orbit with the least amount of fuel expenditure. So, for example, ISS's orbital inclination is 51.6 degrees:

The space shuttle, in order to align with ISS , needs to rotate by 90 + 51.6 = 141.6 degrees (counter-clockwise). Trust me on this. This is orbital mechanics 101. Granted - there may be slight variations on the exact sequence (Looks like shuttle starts pitching while it is still rolling) but the essential principle is: Roll to desired azimuth, pitch into gravity turn.

The amount of azimuth rotation determines the inclination of the orbit. As stated, 141.6 degrees is required to intercept ISS. If the mission calls for a different profile, like a Hubble repair mission, (Hubble's orbit has an inclination of 28.5 degrees), the initial roll will be 118.5 degrees.

Note that anything launched from KSC will have at least 28.6 degrees orbital inclination, as this is the lowest inclination orbit that can be achieved at KSC's latitude (which is 28.6 degrees north). Optimal position of the launch site would be on equator, because from that location, orbit with any inclination angle can be achieved. That's why there was a company called Sea Launch, which would take the whole launch platform out to sea, to the equator, and launch from there.

Re: showing me a video where shuttle starts pitching right away, on the pad: There are 100s of videos of shuttle launches that show shuttle (or any rocket) going straight up for 10 or so seconds, before starting to roll. Are you telling me you will search for one video that shows otherwise, to convince me that 100s of videos are wrong?

Last edited:

Christian Bahr

Resource contributor

- Messages

- 1,103

- Country

And let someone say that scenery design isn't rocket science

@Misho

@ Dean

In case I ever plan a Mars mission project and for whatever reason Elon is unwell, I'd be in very good hands with both of you!

But it's interesting to see the calculations behind such a project; I really have respect for that. I was born in 1969 – the year in human history when a person (an American) first walked on the moon. Later, as a child, like many others, I witnessed rocket launches. Later, the launches of the shuttle missions. Probably for this reason, but not only, my fascination with aviation and space travel is unstoppable.

@Misho

@ Dean

In case I ever plan a Mars mission project and for whatever reason Elon is unwell, I'd be in very good hands with both of you!

But it's interesting to see the calculations behind such a project; I really have respect for that. I was born in 1969 – the year in human history when a person (an American) first walked on the moon. Later, as a child, like many others, I witnessed rocket launches. Later, the launches of the shuttle missions. Probably for this reason, but not only, my fascination with aviation and space travel is unstoppable.